GATHERING 5 Warwick Street London

Gathering is pleased to present phantoms all around me, Matthias Groebel’s debut solo exhibition in the UK. The paintings on view were produced between 2003 and 2006, where Groebel transferred recorded video footage onto canvas using a custom made painting machine.

Groebel had been producing machine-assisted paintings since the late 1980s, continuously refining and improving his infamous painting machine. Assembled from scrap metal, one could visualise the machine as a kind of airbrush attached to a plotter, moving in layers across a canvas providing precise control over the application of acrylic paint. By the turn of the millennium, Groebel, who until then had been capturing images from broadcast television in his paintings, had grown weary of the increasingly manicured studio productions that were taking over German television. Dissatisfied with the loss of the raw, authentic portrayal of the human condition, he turned to the city. Armed with a portable consumer camera and a stereographic filter, he wandered the streets of his native Cologne, London and New York. Groebel would then isolate singular frames from the hours of recorded footage, selecting images that had burned themselves into his memory, to transfer onto canvas.

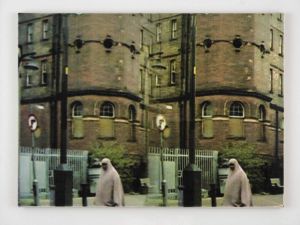

Stereography emerged as an attempt to capture three-dimensionality in two-dimensional images almost at the same time as photography itself. By capturing a scene from different horizontal positions – like human eyesight – it seeks to emulate the natural process of vision. In Groebel’s stereopaintings, two image halves depict the same scene from marginally different perspectives. However, just like the brain that merges the single images into a cohesive plane, stereo photography relies on the use of external viewing devices for the three-dimensional effect to function, 3D cinema glasses perhaps being the most widely known example. This means that Groebel’s paintings, too, contain a sort of spatial information that is usually lost in photography. But without a viewing device large enough to unlock the information, it remains an eternally inaccessible code, an undecipherable message in plain sight: a medium without the technology to make it usable.

The works on view at Gathering stem from footage Groebel shot during his visits to London’s East End. Captured predominantly in Whitechapel, a historically working-class and ethnically diverse borough on the margins of London’s aggressively emerging banking district, many of them feature Tower House, a seven-storey building resembling something between a prison and a palace. Erected in 1902 by Lord Rowton, Tower House provided temporary, low-cost lodging for industrial workers and was known as the “working man’s hostel” or even “ the working man’s members club”. Built in response to the housing crisis of the 1880s, it was meant to provide a “model of hygiene and order”, with large common areas and single cubicles instead of private rooms. The peculiar layout of the building long prevented Tower House from being converted, leading to its dereliction throughout the 20th century.

Groebel captured the building for the first time in 2005 and continued to do so over the next few years. During this time, the sale of the property and the beginning of its conversion to upscale apartments is traceable. The six-panel painting tower house, using images from 2005 and 2006, depicts Tower House before and after its acquisition. On the left panel, its mighty facade is visible as a relic of the neighbourhood’s history. On the right panels, branded scaffolding seals it off from the public. Alongside the spatial information captured by the stereography, the works also encapsulate an element of temporal shift. The rapid change of Tower House can be read as symptomatic of the development of the area during that period.

Groebel’s urban meandering plays into a specific genre of British psychogeography, first born out of Italian and French Situationist vocabulary and adapted through figures like Alain Sinclair or Patrick Keiller from the 1980s onwards. The feeling of walking on foot, the ground-bound subject in the beast of the city under the iron fist of capital, seems especially relevant to the subjective experience of post-Thatcher London and its neoliberal consolidation under New Labour. Much like the stream of nameless faces Groebel chose in his earlier TV paintings, the face in question was now that of a rapidly changing interface of European cities at the dawn of the End of History.

Alongside the painting works, the video work Divine Invasions (2006) is presented. It can be read as a quasi-biography of Philip K. Dick, constructed solely from third-party accounts of the author, deliberately avoiding the mention of his name. Dick, the anonymous protagonist, haunts the narrative. The superimposed moving image footage, shot by Groebel himself, uses the same stereographic technique as seen in the paintings. The spatial shift becomes more pronounced when set in motion, enhancing the experience of simultaneous presence and detachment of Groebel’s subjects.

Text by Dara Jochum Installation and work images by Ollie Hammick and Blythe Thea Williams