GATHERING 5 Warwick Street London

In 1963, Paul Thek travelled to the Cappuccini catacombs of Palermo, where the mummification and display of human remains has been taking place for centuries. On this visit, he describes the 'corpses decorating the walls, and the corridors… filled with windowed coffins,’ remarking that ‘it delighted me that bodies could be used to decorate a room, like flowers.’ Thek’s delight in this ritualised transformation of bodily matter into embellishment underpins his practice, wherein the art-object, like the Catholic relic, acts as an intermediary between the profane corporeal world and the divine realm that it gestures toward. For him – as in the Eucharistic rites – fragmented flesh becomes a vehicle for holiness. Taking Thek’s ‘delight’ at the ritualised transformation of bodily matter into embellishment as a starting point, Material Rites brings together works and practices that explore the blurred lines between art-object and relic. Each of the works on display in Material Rites presents an engagement with the dissolution of boundaries between person and object, tangible and intangible, desecration and devotion, finding mythical power in ‘dead’ material.

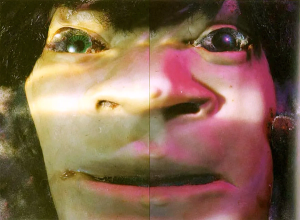

Tai Shani’s practice is marked by an interest in historical – and often forgotten – rituals and communes, organised in structures that contradict the capitalist status quo. She draws inspiration from the documentation of intact ceremonial burial chambers, sites where bodies become matter and the degraded material of clothing, hair and skin mingles with the permanency of stone, jewellery, bone and teeth. Untitled (Skeleton Casket), 2023, invokes this alchemical mixture of objects and matter in the burial site, as an object resembling an elongated spine is adorned with golden talismans and electric flowers that illuminate at the pace of breath. Encased in a glass casket, the structure is both captivating and morbid in its Baroque florescence. Cindy Sherman’s Untitled (#180), from her Disaster series (1986–1989), demonstrates a similarly Baroque mixture of adornment and grotesquery. Its palette is comparable to Shani’s, rooted in galactic purples and pale gold, while the figure’s waxy skin, wide, leaking mouth and frozen expression suggests a body embalmed. Both Shani and Sherman play with the potential of flesh and bone to act as matter, divorcing them from their function as subsidiary components of a healthy, whole human body.

In discussion of Sherman’s work, critic Hal Foster invokes Julia Kristeva’s notion of the abject, which he describes as ‘a category of (non)being.. neither subject nor object, but before one is the first (before full separation from the mother) or after one is the second (as a corpse given over to objecthood).’ Many of the characters that populate Sherman’s Disaster series seem to inhabit this ‘second state,’ as does the relic, an object indelibly marked by its connection to living flesh even as its very existence refuses the wholeness of the body from which it emanates. Katharina Fritsch’s St Katharina (St Catherine), 2003, plays upon systems of affect and fetish closely related to those commanded by the relic as a devotional object. While its scale and synthetic materiality echoes the kitsch of the mass-produced religious statuettes on which it is based, the matte-black surface distances the sculpture from its source material. The smooth, absorptive quality of the pigment is both seductive and impermeable; a shadow or negative of a votive figure, emanating from what critic Rachel Withers describes as Fritsch’s ‘image-world of effigies and doubles, skulls and spooks.’ In a comparable vein, Isa Genzken’s New Building for Berlin, 2001, can be posited as an alternative relic, a fragment referring not to the body of a canonised saint, but instead to a past that is yet to be – a material metonym for a futuristic cityscape.

Claes Oldenburg has referred to his own work as ‘torn-birth flesh-fragments,’ aligning it with Foster’s first category of ‘(non)being.’ ‘Ray Gun’ – iconised here as a lacerated screen print – is at once a category of sculpture, an alter-ego and a wider thematic strain within Oldenburg’s practice, rooted in ‘residual objects.’ In his 1959 Ray Gun notes, Oldenburg praised ‘the beauty and meaning of discarded objects, chance effects,’ declaring that ‘dirt has depth and beauty… Look for beauty where it is not supposed to be found.’ This drive to use refuse as a site of invention runs throughout Robert Smithson’s practice. Before realising his seminal example of land art, Spiral Jetty (1970), Smithson proposed the construction of Island of Broken Glass (1969–70) by Nanaimo, Vancouver. The project, which would entail the artist covering an island with 100 tonnes of green glass shards left to gradually disintegrate into the sand over time, was ultimately rejected. Smithson described the hypothetical work as the ‘physical equivalence of a mental image’; the sketch on display preserves the work in its latter state of potentiality, existing forever in its capacity as a non-place.

Thek’s landscape drawings share this sense of the non-place; unmarked by discernible specificity, the viewer’s understanding of the relationship between the artist and the sites captured in pencil on paper is precluded by a delicate ambivalence. Here – as in Thek’s series of etchings – the broken body, so emphatically present in the artist’s famous Technological Reliquaries, is nowhere to be seen. Instead, with a tone of knowing naivety, Thek constructs his own iconography of burning books, galactic prunes, diving swans, crucifixes and birthday cakes, with quasi-Catholic inscriptions including ‘this is my body’s’, ‘Ave/Eva’ and ‘Tower of Babel.’ Like the tales of Brother Grimm, the series is inflected with a feeling of portentous allegory, where the whimsical imagery of a fairy tale world masks political and personal truths. Executed towards the end of the artist’s life, and discovered, posthumously, stuffed between the leaves of books, the etching series constitutes the ultimate representation of Thek’s personal faith. Intertwining the language of the divine with that of joyful sensory experience, the works remind us, in the artist's own words, that ‘the mystery of the world is in the visible.’

Featuring works by Isa Genzken (1948)Claes Oldenburg (1929 – 2022)Tai Shani (1976)Cindy Sherman (1954)Robert SmithsonPaul ThekKatharina Fritsch (1956)

Text by Sybilla Griffin