GATHERING 5 Warwick Street London

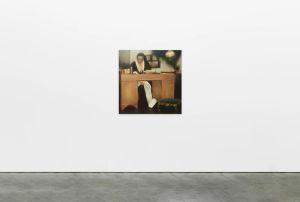

Gathering is pleased to present Love You, Don’t Love You, a retrospective of Tamara K.E., tracing nearly 25 years of her artistic evolution.

In his essay in Tamara K.E.’s 2007 monograph, A Private View, Boris Groys underscores that the artist’s pictorial content, appropriating “contemporary media images”, is “hard to define” and marked by “consistent undefinability, unsharpness, and ambiguity”. The paintings in question included advertising images, stills from Hollywood films and MTV shows and photos of celebrities. Although we do not find such outright digital appropriation in the works comprising Love You, Don’t Love You, Groys’s characterisation is just as apt, demonstrating that this incertitude is one of K.E.’s through lines, which she achieves with a dual act: one that pertains to her shifting, scattered forms, planes and backgrounds while on the other to her vague pictorial motifs.

In Wide-Open (2013), K.E. posits errant lattices and lilac-striated arrays along the corners of a beclouded, soft pictorial field fogged by peach, mauve and russet stroke-based cantons. K.E.’s canvases abrogate both the archival gesture that tethered the Abstract Expressionists’ skeins and splatters to identifiably human movements and geometrical indices, which moored subsequent Post-painterly Abstractionists like Frank Stella and Jules Olitski to the world of geometry and form. There is a veritably digital miasma to K.E.’s paintings, which ICA Miami curator Gean Moreno, termed their “digital surfaces”. The means by which K.E. achieves this gloss of digitality is fairly unclear, after all, the works are executed traditionally, in oil on canvas.

It is not the case that all of K.E.’s works lack pictorial perspicacity. Regenerated Man (2001) is a reminder of punctilious photorealist dexterity, which characterised her portrayals of women from the early aughts. In other works, her clarity is more latent, seamed to suggested forms. Untitled (from the Cool Girls Die Twice series; 2025) adumbrates a woman with twin topknots, her frame reduced to a parcelled silhouette and filled in dust-grey, amber and coral strokes. The two, ear-like mounds of bubble gum-pink hair recall K.E.’s recurrent cartoon rabbit, a motif distilled from narrative chains that she often turns and returns.

According to Groys, K.E.’s opacity is not only proscribed to the domain of aesthetics but also the works’ meanings, her work leaving us barren and abandoned, with no “clearly definable message”. Yet it is not the case that K.E. has deracinated us of all cues as to what her work is about. In Olé, Mexico! (2000), for instance, we are privy to a close-up image of a woman’s pubic hair-tufted groin, where K.E. appropriates Gustave Courbet’s L’Origine du monde (1866). In Olé, Mexico!, a painted miniature is cradled between the fold of her lap. The raised cylindric element, phallic in its connotations, is pronounced against the woman’s nebulous warm skin. Again, it would be inappropriate to retrofit straightforward, literalist feminist meaning onto K.E.’s appropriations. Marjorie Strider made incisive use of such feminist pictorial appropriation; in Green Vertical (1964), for instance, she puckishly appropriated Manet’s A Bundle of Asparagus (1880). But where Strider donned the mantle of a symbolist, K.E.’s symbols merely license a broader engagement with postmodern pluralism.

Groys interprets K.E.’s associative juxtapositions, of world and word—which we might expand to also include formal compositional elements (e.g., Wide Open’s pairing of foregrounded latticeworks and a teeming collapsed background) and figurative content (e.g., Olé, Mexico!’s coupling of a mons pubis and painted tchotchke)—as motivated by “a pure lust for association”. For Groys, K.E.’s pluralism is in keeping with the disinterested stance, where the artist is but a “modern end-user”, or “model viewer”, at liberty to “examine, enjoy, and comment”. K.E. is not, Groys tells us, a socio-politically committed symbolist but a pure aesthete, producing images that betray taste for taste’s sake. But it is not the case that K.E.’s work hews exclusively towards aesthetic delight. Were this the case, she would exclusively paint forms betraying “uniform design”, which philosophers like Lord Shaftesbury, Francis Hutcheson and Joseph Addison identified as integral to aesthetic pleasure.

K.E.’s deportation of images from any “clearly definable message” makes for a clearly definable message itself. Her paintings dissolve motifs, forms and planes into equally instrumental pictorial elements. Groys avers that K.E. “manipulate[s] images as big, modern administrators manipulate all sorts of data”. But by treating constituent motifs alongside planes, forms and styles as material rife for pictorial association, K.E. embodies her work with meaning. She does not sap it of meaning. The works are about the postmodern condition, which finds art history abdicated of orientational narratives. This includes the pre-modern orientational narrative of perceptual verisimilitude, inaugurated in ancient Greece, rejoined during the Renaissance and deemed “realism” during the nineteenth century only to be displaced by photography and cinema. The collapse of this orientational narrative gave rise to that of Modernism, which hewed towards the discovery of that which essential to painting, qua painting. Modernism was, in its Greenbergian idiom, oriented towards that which could be perceptually described—i.e., the canvases’ virtual flatness and the structure of the support. This orientational narrative, however, was displaced by Warhol’s 1964 Brillo Box, which stopped modernism—and, by consequence, the progressive view of art history—in its tracks. For the Brillo Box enjoyed the categorial status of an “artwork” not by dint of its discernible content (as it was perceptually identical to its real-world counterpart, bought and sold in supermarkets) but, instead, due to its embodied meaning.

Thus, as Arthur Danto theorised, Warhol’s work not only halted Modernism but the possibility of future orientational narratives, marking the “death of art history”. For Danto, this was liberating. And so commenced the epoch of pluralism, with art history at once divested of any goal or direction and, accordingly, acquiring a plenitude of novel freedoms. An artist could wake as an Abstract Expressionist, lunch as a Photorealist, take an evening stroll as a Pop artist, only to dine as an Impressionist. K.E.’s work thatches together these pluralist vernaculars, interlacing them in a pictorial montage, a “kaleidoscope of delirium”. In so doing, K.E.’s embodies her pluralist amassment with meaning: one that attends to and is subtended by the pluralist postmodern condition that it reflexively enjoys.

Text by Ekin Erkan Photography by Ollie Hammick