GATHERING 5 Warwick Street London

Hailing from Pryor, Montana, Portland-based artist Wendy Red Star (b. 1981) is an enrolled member of the Apsáalooke (Crow) Tribe. Her artistic practice is deeply rooted in her upbringing within Apsáalooke culture, while also drawing inspiration from conceptual art strategies, pop culture, museological traditions, and the reconfiguration of colonial narratives. On entering the gallery, visitors encounter what appears to be a paper mountain range, occupying the entirety of the ground floor space. The installation takes its design from that of an inexpensive, mass-produced greetings card – the kind that, when opened, folds out into a three-dimensional pastiche of a generalised natural landscape. Constructed from Valchromat MDF, the installation marries the cursory visual language of theatrical scenery with elements of geographical specificity: the paper mountains bear flora and fauna, canyons and topographical details referring directly to the Pryor Mountains, animated by a recording of the landscape’s sounds: layers of birdsong, insects, running water, the rustle of bodies moving through grass.

Forming the western boundary of Montana’s Crow country, the Pryor Mountains are a site of Apsáalooke history and folklore, with an especial significance to Red Star - standing at the heart of the reservation on which she grew up. In a 2007 letter to the Supervisor of Custer National Forest, George Reed Jr. (former Chairman of Crow cultural committee) writes ‘the mountain ranges in the territory of the Apsáalooke (Crow) Nation are sacred because that is where First Maker travels as he watches his creation,’ while the late John Pretty On Top, a Crow traditionalist, describes the Pryors as ‘a cathedral without a roof, without a wall.’ As Red Star has noted in previous writings, the notion of the ‘live relic,’ posited by Cree artist Kimowan Metchewais (1963–2011) is a useful lens through which to understand the significance of Pryor within Crow culture. In discussion of his own ‘live relics,’ Metchewais writes: ‘they are relics because they are like trace elements from memory, history and culture [;] they are alive because they continue to transmit influence to this day.’ As Red Star collapses this live relic into the form of a souvenir pop-up card, installed thousands of miles from its origin, she plays with the language of museological display, transforming what would more commonly be used as a backdrop or teaching aid into an immersive installation.

The gallery’s lower level is occupied by Red Star's 2016 sculpture titled Tokens, Gold & Glory, composed of gold Mylar, headless deer hunting decoys, astroturf, and wooden pallets. As in the ground floor installation, Red Star uses synthetic, low-grade materials that jar against the natural imagery being represented. In doing so, the artist wryly plays with notions of ‘authenticity’ in relation to what is expected or assumed of a Native artist’s output. Across both works, it becomes clear that Red Star’s humorous tone does not preclude poignancy: despite the obvious artificiality of the dummy deer and the plastic grass, the spectacularised violence of the decapitated animals, obediently standing on their exhibition platform with mylar blood gushing from their necks, is imbued with a strange pathos. Rendered in green and gold – the elemental colours of American capital and expansion – Tokens acts as an inverted hunting trophy, a vision of what is left behind after pelts have been stripped and antlers have been mounted to the wall.

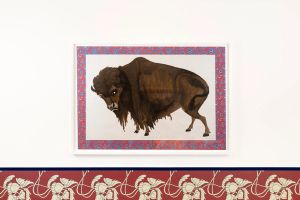

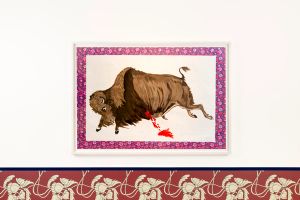

The buffalo depicted in the paintings displayed alongside Tokens possess the visual markers of expression and affect that the headless deer are denied: bodies twist in movement, eyes roll, blood drips from thick fur. Each buffalo is copied from George Caitlin’s (1796–1832) series of buffalo paintings – a lawyer and artist who became infamous for his documentation of the American West, through portraits of members of the Plains tribes (including the Crow), landscape painting, and the collection of objects amassed during his travels that he used to form his ‘Indian Gallery,’ now in the collection of the Smithsonian Museum. Red Star used Caitlin’s buffalo paintings as a departure point, contrasting them against contemporary Native depictions of the animals, noting the ways these representations diverged. Of the latter, she says ‘all the buffalo, even though some of them are wounded, seem happy. They’re frolicking, and then you get to Caitlin’s, and his buffalo are in agony, pure agony.’ The series exemplifies a significant strand of Red Star’s practice, based in the activation of images and objects found in museum archives, fleshing out their context and allowing them to speak across time.

The wallpaper that adorns the gallery walls is replicated from cloth decorating the home of Plenty Coups (1848–1932), the last chief of the Crow Nation. Installed in the chief’s private room, the fabric covered the lower portion of the wall, a positioning that, according to historian Timothy McCleary, referred to bitdalasshia: cloth that would traditionally line the lower portion of a Crow tipi, aiding with ventilation. The vermillion, foliate design could be seen as reminiscent of the decorative styles popularised in the UK by the Arts and Crafts movement, but for Red Star, constitutes ‘the epitome of Crow aesthetic. Florals remind me of my grandmother and her designs for beadwork and shawls.’ Again, Red Star undercuts the notion of an ‘authentic’ (read: static, homogenised) Native visual language that has been sought after or constructed by colonialist anthropology and media representation, capturing instead the specificity of Crow material culture.

As the decimation of the buffalo population can attest, the Pryor mountains still bear the ruptures of the American frontier: hunting, the early fur trade, and the westward railroad expansion. They are also inscribed with Red Star’s personal history and the communal histories and myths of the Apsáalooke people; throughout In the Shadow of Paper Mountains, we are reminded that landscape holds history and sustains it, translating it into the living present.

Text by Sybilla Griffin Installation images by Ollie Hammick Work images by Blythe Thea Williams