GATHERING 5 Warwick Street London

Emanuel de Carvalho’s paintings and sculptures challenge preconceptions as to how we perceive and relate to the world around us. With a background in medicine and neuro-ophthalmology, the artist uses his practice to research perception as a psychophysical phenomenon, exploring the ways in which it is shaped by social norms and constructs. Drawing on this background as well as philosophies of being and perception, De Carvalho’s work is underpinned by his conviction that ‘within the fabric of societal constructs and established norms lies the potential for transformation –– brought about not by sweeping revolutions, but by the subtle insurgency of ideas, narratives, and expressions.’

The title of De Carvalho’s first solo exhibition at Gathering, ‘code new state’ references the authoritarian ‘Estado Novo’ regime that governed Portugal until 1974, while also suggesting that other states (of mind, being, etc.) can be possible if only we take the time to reflect on our habits and behaviours. The uneasy coexistence of both oppressive control and hopeful transformation that the title suggests lies at the heart of the works in this exhibition.

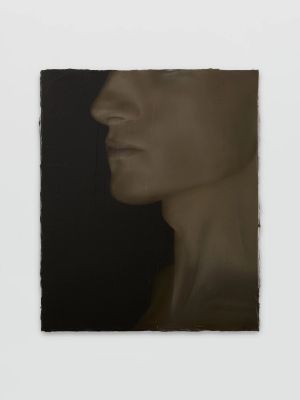

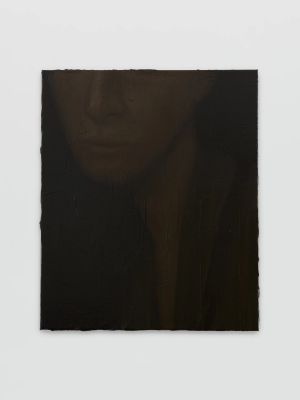

De Carvalho destabilises perception while liberating it from any one idea of what it can or should be. Throughout the works on display, spaces are subtly warped and distorted, entrances and exits are implied, yet neither full access nor complete exit seem possible; we feel both trapped and excluded simultaneously. And yet, amidst these uncomfortable renderings of spaces, we become aware that there can never be a single, complete view of reality.

In unground lack and ground lack, for example, De Carvalho paints empty lecture halls, evoking the institutional atmosphere of formalised education. In both, De Carvalho uses slight alterations in perspective and includes reflections contrary to where we think they ‘should’ be. In so doing, the serried ranks of seats and the sombre architecture of the lecture hall seems to slip from a sense of order and hierarchy into a dream-like world of incompatible perspectives and visual effects. This sense of dreamy or nightmarish incomprehensibility at the heart of order and structure is further evoked by the titles of these works, which reference Heidegger’s concept of ‘ground’ (Grund), the foundational essence of existence from which all things derive meaning, and ‘unground’, or abyss (Abgrund) the unfathomable depth of Being beyond human understanding.

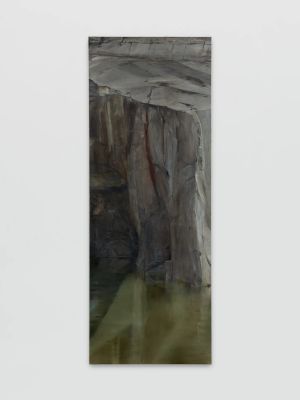

De Carvalho further explores the latent sense of confusion and disorder in the monumental work, code lack. An almost baroque distortion of scale, warps and confuses the structure of figure-ground, foreground-background, proximity and distance: the wall appears to loom both vertiginously into the viewer’s space and recede into the picture plane, its variegated texture appealing intimately to our sense of touch while also feeling distantly unfamiliar. A human figure, which might have grounded our sense of scale, only confounds our understanding of the space as they do not seem to fit proportionally into the environment around them. Playing further with perception, in the sculptural installation downstairs, lack slit system, De Carvalho has made a monumental cube that appears to exert power over the space and implies surveillance. Although reminiscent of the centre of a panopticon prison, the sculpture only frustrates panoramic surveillance: crawl inside, and the opening above is inaccessible and we find ourselves alone, in darkness, as if in the very cell the structure may have been intended to scrutinise.

Indeed, contrary to the dream of panoptical vision, De Carvalho’s works are not constructed for one privileged viewer. Standing before his paintings, we have to shift back and forth, this way and that, each time encountering a different perspective point while never finding the moment where the whole work coalescences into the clear and ordered legibility we might find in the one-point perspective of a Renaissance painting (see for example the multiple perspectives and atmospheric light effects used in constancy lack and transfer lack). Instead, the relationship to the scenes he creates is dynamic and variable. Like collage, perspectives are brought together on one plane, although unlike collage these different points of view are smoothed together as if the scene were spread across a pliable surface as on a liquid screen or textile. The very idea of a perspective ‘point’ starts to dissolve in De Carvalho’s work: perspectival space appears to follow not lines, but swirls and bends, close and intimate and then distant and ungraspable, a disconcerting effect not unlike running toward an ever-receding horizon in a nightmare.

This is what makes his works strangely familiar, recalling the experience of being in a fever or entering a space we do not quite know how to move through, such as a new house or a potentially hostile crowd. Looking at his works, we cannot feel self-assured with our gaze. Smudges and stains, like the reflection of light on a window stop our gaze short (look at the bottom left of unground lack for example) so that as much as we try to be absorbed in a scene by looking into it as if it were made for us –– the modus operandi of realism –– we are only then propelled back onto the surface of the painting. Techniques such as mixing ground pumice into the paint further draw attention to the surface of the work, while also lending the paintings an atmospheric patina, as if we are confronted with paintings from another era, perhaps from the baroque period with its bewildering contortions of space. If the influential Renaissance artist and theorist Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472) proclaimed that a painting should act like a window onto the world, de Carvalho makes us look as much at the window as what lies behind it. Wavering disconcertingly between the submission to an illusion and the awareness of the mechanisms of that illusion, we are reminded that neither representation nor perception are a neutral fait accompli; they can be played with, distorted, transformed.

This approach to perception emerges from the foundational experience that De Carvalho’s had working with patients with certain neurological conditions whose experience of reality was fundamentally different from his own. He realised how just as all of us perceive the world differently by various degrees, reality can never be ‘caught’ by one representational regime. For De Carvalho, perception and being in the world is dynamic and processual, evolving interdependently with the world as we move through it. He reminds us that we do not so much grasp a space as grapple our way through it.

In this respect De Carvalho shares an understanding of perception with the philosopher Catherine Malabou, a future collaborator, who has inspired, together with UCL Professor of Neurology, Parashkev Nachev, a set of new sculptures that will be gradually revealed inside in the long, table-like sculptural work, lack skill I. Malabou’s concept of plasticity has had a particular impact on De Carvalho’s work. The notion is derived from developments in neuroplasticity (the brain’s ability to reorganise itself by forming new neural connections throughout life in response to changing conditions, such as trauma and learning) and suggests that our behaviours and habits, like perceptions, can be moulded and reshaped in response to environments and experiences. With their disorienting spatial renderings which draw attention to the act of looking itself, De Carvalho’s work compels viewers to be attentive to such possibilities of ongoing processes of transformation and adaptation to how we relate to the world. For De Carvalho, as for Malabou, plasticity is therefore rooted in an ethical principle of transformative potential, openness and responsiveness (or, as the philosopher and physicist Karen Barad would put it, ‘response-ability’). As those who have been marginalised are well aware, relations can be –– indeed must be –– transformed beyond the assumptions and attitudes that attempt to fix human and nonhuman beings in rigid categories and places.

De Carvalho’s perceptual disruptions are not then simply visual games but attempts to shift our relationship with how we perceive and relate to the environment and others. To be truly alive to the world, De Carvalho suggests, one can only tread carefully as if we are not quite sure of where we are going or what we are perceiving, just as we may feel we can never quite fully comprehend the disorienting spaces he creates. This incipient sense of lack of understanding and knowing (‘lack’ is a word that De Carvalho uses to title several of his paintings) can itself be moulded into a creative form of anxiety, one propelled by a sense that we can never have a totalising grasp of the world and others around us. But in eluding our grasp, De Carvalho reminds us that the world is not there to be possessed and fixed as if it were a static object or commodity, but one to be encountered again and again. With each encounter our modes of understanding can be shifted and our body-minds transformed through new codes of behaving and new states of being.

Text by Yates Norton Installation and Work Images by Ollie Hammick